Happy Halloween all. Tallulah is out Trick-or-Treating, by which I mean she turned a trick she felt was quite a treat, and now she's out --- cold. So while she's napping, I'd like to tell you about the man who was Halloween Personified to me: Larry "Seymour" Vincent, who is 32 dead years dead, but forever alive in my heart.

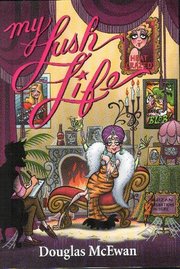

I don't think I've mentioned that I've written and published a new book,

The Q Guide to Classic Monster Movies. What? I have mentioned it? Okay. It's a Halloween-type book. I'd like to share with you the words found on the dedication page. They are:

Jerry Vance was born in Boston in 1924. Early in his career he adopted the name Larry Vincent, but when he died all too young at 50 in 1975, he was best known as Seymour, The Master of the Macabre, The Epitome of Evil, The Most Sinister Man to Crawl Across the Face of the Earth. And the Best TV Horror Host that ever was. He was also the first person to pay me to write jokes about horror movies, and he was my friend. I miss him still, and I dedicate this book to his memory.

A photograph of Larry and myself was supposed to appear on that page, but was cut without my permission, or indeed even any notification to me. I found out it was not in the book when the I received the first copy. This is one of several matters concerning the treatment my book received from it's publishers which have left me - let's say dissatisfied. Anyway, here's the picture that was supposed to be in the book.

A strange thing happened a couple days before the book came out. I was channel surfing one afternoon less than a week before publication day, and I came across an episode of Mission: Impossible from the third season, shot probably in 1968 or '69. This seemed like just the mindless white noise I wanted running. A few minutes into it, a door on the TV screen opened, and Larry Vincent stepped into the show and began playing a scene with Martin Landau.

I knew that Larry had appeared in an episode of Mission: Impossible, but not that I was watching that episode, so his appearance surprised me into happy tears. There was my long-dead friend, alive and acting with a future Oscar winner. And Landau's Oscar was for playing Bela Lugosi, an actor, and I use the term loosely, who is profiled in my new book, (Have I mentioned I have a new book out? Just checking.) dedicated to Larry. It was a wild series of accidental occurrences, but it felt to me like a ghostly visit from my friend, a Hello to acknowledge my posthumous gift. Incidentally, that episode, from season 3, comes out on DVD in December. I'll be buying it. So can you.

I'd like to share with you this Halloween an account of my friendship with this wonderful and funny man, which I wrote 7 years ago for the

Local Legends webpage, about Los Angeles TV personalities of the 1950s, '60s, and '70s. Believe me, if there'd been no Seymour, there'd never have been Elvira.

Having been a big fan of

Jeepers Creepers (A hosted horror movie TV show in Los Angeles from 1962 to 1965.), when I was ages 12 to 14, when a new horror host show,

Fright Night With Seymour came on KHJ in 1970, I was excited to tune in, and quickly fell in love with Seymour's prickly sense of iconoclastic humor. I was in college at the time, and never guessed that before Seymour ran his course, I would become a part of it.

Seymour was so popular with us college kids, that we actually turned on the show and watched him, even at parties. I remember the night I turned 21, in May 1971, I performed as Puck in the closing night performance of our University production of A Midsummer Night's Dream, then went to the closing night party at the home of the girl playing Hermia in Hermosa beach, and very stoned, we all watched Seymour. We talked through most of whichever movie was running, and we ignored the commercials, but we all watched Seymour and laughed our heads off.

I first actually met Seymour that October, the night the opening day at Disney World TV special was broadcast. Seymour was hosting a special Halloween show at the Wiltern Theatre: a double feature of The Return Of Count Yorga & Night Of The Living Dead. Seymour did a monologue, including his infamous version of The Raven, then sat onstage with a microphone and made jokes all through the silly Count Yorga sequel. (Whatever possessed AIP to think that queeny Robert Quarry could be the next Vincent Price?) During intermission Seymour signed autographs in the lobby. Then he introduced the second feature, mentioning that jokes wouldn't be appropriate during George Romero's disturbing masterpiece, and left.

I stood in the fan line and got Seymour's autograph on my Seymour certificate and went home thoroughly entertained. Over the next couple years I attended several more Seymour appearances in movie theatres, and seeing some real dogs in the process. But the day came, in late 1973, when Seymour was announced to ride in the Westminster Founder's Day Parade, a parade which formed on the grounds of Westminster High School, from which I had graduated in 1968, just a half mile from my home.

I was working then writing radio comedy for "Sweet Dick" Whittington at KGIL (To this day, still a close friend), and decided to take a shot at getting a writing spot with Seymour. I was convinced I could write the character. I'd seldom missed the show, and felt I knew the character intimately by this time.

I found Seymour waiting around, just outside a classroom in which, a few years earlier, I had studied Moby Dick & Lord Of The Flies. I introduced myself to Larry Vincent, told him I was writing for Sweet Dick, and asked if he was looking for writers for his TV show. Luck was in. He was. He told me to call his office on Monday and set-up an appointment to come in and show him some sample material. He also introduced me to Lynda Vincent, his much-younger wife, who wrote most of the shows with him, and Gary Blair, the show's executive producer, who was also the voice of Herkamer Eugenski, the nasal voiced, whiny announcer for Seymour Presents on KTLA.

I made that call, come Monday, and Larry, who was as nice on the phone, as Seymour was prickly on the air, invited me to come down to the studio a few days later, on the day they would be shooting that week's show. I could show him my samples and watch a Seymour show shot. I was in Heaven.

The evening before my appointment, I sat down and made a stack of what I felt were my strongest radio sketches. Then I put paper in the typewriter, and wrote a sample Seymour sketch.

At that time, one of the most popular shows on the air on KTLA was Help Thy Neighbor. Neighbor was a morbid feel-good tearfest, on which down-on-their-luck sad sacks would come on, unload their sob story to the host, Larry Van Nuys, and then Larry would take phone calls. Viewers (The show was on live, 5 nights a week) would call in with one form of assistance or another to help the poor schmuck humiliating himself. It was creepy and smarmy, only slightly less horrifying then Queen For A Day. (At least everybody who came on got helped. They didn't kick 3 needy cases out empty-handed each day like Queen did.)

I felt that Help Thy Neighbor was ripe for the Seymour treatment. I wrote a sketch called Shaft Thy Neighbor, in which Seymour read a letter from a pathetic wretch who had been buried under the biggest pile of hard luck since Job, and then took calls from people who "Helped" him, by making matters worse. ("You will no longer have to work day and night at two jobs to support your wife and 14 shoeless children, because your bosses both phoned and fired you, your wife has left you for another man, and your children have all run away.")

When I got to the KTLA lot at Sunset & Van Ness (Just across the street from an apartment building, now demolished, in which I was to live in 1986-8. It's the apartment building in Pulp Fiction.) Larry brought me in to to see The Slimy Wall in the sound stage. To my delight, the Help Thy Neighbor set sat right next to the Slimy Wall, at right angles to it. My sketch could be shot on the actual set, just by rotating the cameras 90 degrees!

As we entered the studio, we ran into Larry Van Nuys coming out. As it happened, I knew Larry Van Nuys. Prior to his achieving 15 minutes of stardom with Help Thy Neighbor, he had been the next disc jockey on after Whittington each morning at KGIL. (Since leaving, he'd been replaced by Wink Martindale) Larry Van Nuys, seeing me, hollered, "Douglas! How the hell are you?", and grabbed me in a big bear hug and gave me a loud, sloppy kiss on the cheek, all right in front of Larry Vincent. I explained that I was there to try and land a job writing for Seymour, and Larry Van Nuys, on the spot, began to regale Larry Vincent with extravagant praise of my comic genius. This, I felt, didn't hurt at all

Larry Vincent explained that he had been actively trying out writers for sometime, to find someone to take the burden of turning out the scripts every week off his and Lynda's shoulders. In fact, the show I was going to see shot was written by a female guest writer, to whom I was introduced. I instantly envied and hated her.

Back in his office, I gave Larry my sample pile, with the Seymour sketch carefully buried at the bottom. I sat there as Larry read the pages. He started looking stern and detached, but quickly was laughing out loud, and mentioning how funny he found some of the words used. (I remember him saying he thought "Dreck" a particularly funny word, when it popped up in one of my sketches.)

Then he came to Shaft Thy Neighbor. "What's this?" he asked. I explained that it was a sample Seymour sketch I'd written the night before, to show how well I could write for him. He put his serious, detached face back on, but it didn't stay long. By the time he finished reading the sketch, not only had I been commissioned to write an entire script, but Larry bought the Shaft sketch on the spot.

The movie I was assigned to write a show around was

The Leech Woman. Unfortunately, it was not possible for some reason, for me to see the movie before writing the script. (The evening my show was broadcast remains, to this day, my only viewing of

The Leech Woman, a film of seminal importance to my career.) I looked the movie up in several guides, and read as much about it as I could, and went from there.

Since I couldn't write about the film's specifics, I wrote instead a series of parodies of other famous films & TV shows. My opening sketch was a take-off on

You Bet Your Life. When Seymour said "Fringies", that turned out to be the secret word, and a rubber chicken came flying down from the eaves. Another sketch employed a huge photo of Banjo Billy I had seen on Larry's office wall, which, in my script, became Dorian Gray's portrait of Seymour. ("Many of you have commented on how I appear to be eternally youthful, how my classically chiseled features never show the wear of time.") Of course, when Seymour revealed the picture, he was livid. ("That can't be me! I want my money back! Eternal youth isn't worth that! Get me Dorian Gray on the telephone immediately!")

I had Seymour try to crash That Party Down The Block disguised as a mousekateer, wearing my own, personal mouse ears, and a furry shirt that had been part of a theatrical costume of mine. (Lynda Vincent provided the offscreen voice of Annette). Shaft Thy Neighbor was used, and, in my favorite sketch, a parody of Curt Siodmak's beloved Sci-fi nonsense Donovan's Brain, I had Seymour remove Eugenski's brain and put it in a fish tank. The disembodied brain instantly took control of Seymour, forcing him to tap dance and sing Won't You Come Home, Bill Bailey. In the final scene, Eugenski's brain had been put in Seymour's body, so Seymour now spoke with his squeaky voice, while Seymour's brain squawked impotently from the tank. In short, since this might be my only Seymour script, I fired all my comedy guns.

I delivered the finished script to Larry at the Equicon science fiction film convention, that November. My relationship with Larry had already altered. It was no longer fan and celebrity. Larry let me hang with him throughout the convention, and we discovered that I had the ability to break Larry up as easily as he broke me up. We were to go on breaking each other up, for the rest of his life.

Unfortunately, when the time came to shoot the script, Larry had bad news. KTLA had cancelled him. My script was to be his next-to-last show. Larry told me he was very happy with what I had written. He said they had auditioned dozens of other writers and every single one of them had had to be completely rewritten by Lynda and him to fit the character's speech patterns and stay in character, which meant they saved them no work at all. Mine was the only script anyone else had ever written for them that could be shot exactly as written, with no rewriting. The job would have been mine, except, there was now no job.

One change had been made. KTLA Standards & Practices decided that Shaft Thy Neighbor was dirty. (It was 1973. Dinosaurs still walked the earth) The sketch was changed to Shelf Thy Neighbor, which sounds similar, but which, you'll notice, makes no sense.

On KTLA we had a set time slot. The show had to end on time. As we shot the show, it soon became clear that my script was too long. Midway through shooting, the film editor went back to his lab and hacked a few more minutes out of The Leech Woman, to give us some more air time. (So disrespectful. Fortunately, the movie is crap) Even with the movie butchered to bits, there wasn't time for my brain switch ending. Seymour's brain would remain in his skull. Too bad.

My friend, the late David Tarling, came to the taping with me and took these pictures, now so precious to me. The one picture from that day that I no longer have, was a shot of Larry, Lynda, Garry and myself, lined up in front of the Slimy Wall. Months later, when I began working with Larry at his home on a projected record album, I was proud to see that picture of us framed on Larry's living room wall, where it remained until his death.

So, that was it, I thought. The day of the broadcast, in January 1974, I had friends over and we and my family all watched my first, and for all we knew last, show air. At one point, after an unseen, imaginary audience boos a particularly lame joke, Seymour said, "I didn't write that joke. I got it from Eugenski, and he got it from his writer, whom I've already fired." My mother broke up and, always willing to ally herself with anyone criticizing me, said, "He really let you have it for that one." I believe she was disappointed when I showed her that every word of that bit, including the booing sound effects, were in the script and were written by me. Mother was so hoping it was Larry departing from the script to humiliate me on TV.

Shortly thereafter, I was promoted to producer of The Sweet Dick Whittington Show at KGIL, which was now full-time employment, writing bits, booking the interview guests and setting up all the details of Dick's notorious live stunts. I became happily busy.

At the beginning of March Larry Vincent called me. KHJ had picked the show up. Back under it's original title Fright Night With Seymour, it was going back on the air in April, and Larry was putting me on staff to write half the shows. Best of all, our time slot was open-ended. It didn't matter how long we ran, so I could write as long a show as I wanted and we would do it all, without butchering the movies. You've heard of a dream come true? Well, this was one.

We shot every other Thursday afternoon, doing two shows in a session. Every other taping session I would be the author of the shows. The two shows in between would be by Larry & Lynda.

I would come in to the studio and sit in a screening room so tiny it made the Marx Brothers stateroom look like a stateroom, and a projectionist would run 16mm prints of my two movies. In this pre-home video Stone Age this was the only chance I had to see the films, though a couple, like The Incredible Shrinking Man, which was the best film we ran, I already knew fairly well. I took extensive notes of everything that happened in the movie. I wrote the scripts at my leisure, usually in my office at KGIL, turned them in, came in the day before taping and met with the projectionist/editor, with whom I would extract the film clips we would be using in the show. Since we literally snipped the clips out of the movie, and spliced them back in when we had shot the show, we were damaging the prints every time we used a clip. Naughty.

I came to all the tapings, whether it was my shows or not, for two reasons. 1. I often came up with tweakings for lines or bits on the set, and 2. Being with Larry was such a joy I wanted to be around all I could.

Larry was a great guy, and we became close friends quickly. Lynda & Garry were also terrific people, and we were a happy unit indeed. Larry had a temper. If somebody screwed something up, he would let them have it with both barrels, but he never simply got angry, and he never got angry without cause. In all the time I knew him, he never once raised his voice to me.

In May, Larry rode in the Strawberry Festival Parade in Garden Grove, not far from my folk's home in Westminster. I rode in the parade with Larry & Lynda, then we went to my parent's home for a huge home cooked meal. My 16 year old brother Duncan had, of course, told every kid for miles around that Seymour was coming to our house, so there was a small crowd of kids to greet us when we arrived. (Enroute, we had stopped at a K-Mart to pick something up, and Larry had been recognized, and started a small mob scene.) Larry & I got going at that meal, sharing increasingly ribald humor, while Lynda & my mother sort of smiled indulgently. (I remember one thing that broke us up being the idea of Larry playing Banjo Billy wearing, instead of Groucho glasses and fake nose, a dildo-nose & glasses. Well, it is a funny image, though Mother wasn't amused.)

We attended a Sci-fi/comics convention in San Diego together, during which, they ran Larry's ghastly movie The Witchmaker. Larry and I sat and made jokes aloud throughout the film to the delight of the audience.

(In an excessively weird co-incidence, at that time, I was working for Larry Vincent, who had appeared in The Incredible Two-Headed Transplant, and Sweet Dick Whittington, who appeared in The Thing With Two heads. Stranger still, now those two two-headed movies are available on the same DVD. It's like my 1974 life on one disc, with my one boss on side 1, and my other boss on side 2. Spooky.)

Killing two jobs with one stone, I booked Larry on The Whittington Show on KGIL one morning as an interview guest and sat back and listened to the comedy gold as my two bosses sparked and riffed together, the only time they ever met. (Needless to say, they both tried to top each other with tales of what an utterly worthless excuse for an employee I was.)

One time on the set, a sketch required Larry to wear a Sherlock Holmes-type deerstalker cap. He was wearing my own personal one. (I kept writing my wardrobe into the show) Larry was in place on the set, waiting for the scene to be slated when I strolled up to him and whispered to him that he had the hat on backwards. Now, of course, the front and back of a deerstalker cap are identical. It isn't possible to put it on backwards, though you can wear it sideways, as Harpo does in Duck Soup. Larry knew this, of course. But he strode mock-angrily off the set, and staged a pretend tantrum ("Why doesn't anybody check these details?") about almost being allowed to do the sketch with the hat on wrong, while he took the hat off, turned it around, and re-groomed.

May 1st, 1974 Doodles Weaver was on the set. He had recently released a record album called Feetlebaum Returns, and was now going to produce a Seymour comedy album. Larry and I were to write it. That evening I dined with Doodles and Walker Edmiston, and Doodles regaled us with tales of drinking with Bogart. Doodles was a great guy to hang with, but murder to work with. We argued about material constantly. Basically, I would write a Seymour piece and Doodles would rewrite it into a Doodles piece, and then, since Larry would be doing it rather than Doodles, it got changed back to my original version.

I remember one afternoon, sitting with Larry in his living room in Santa Monica, working on the album script, when Larry and I noticed something odd. Visible through his sliding glass door, a wrench was floating up into the air. Larry had an open toolbox on the porch, and we found a kid leaning out of the window of an upstairs apartment, with a fishing rod with a magnet on the line, tool fishing.

Larry was appearing six nights a week at The Mayfair Music Hall in Santa Monica most of that year. As it was easier than bringing people to the studio, I often took friends to the Music Hall to meet Larry and see him perform live, seeing and meeting guest performers as varied as Ian Whitcomb and the late, great Anna Russell. Bernard Fox, who more recently appeared in both Titanic and the Brendon Fraser version of The Mummy, was the Master of ceremonies for these shows.

Once Larry tipped me off that Mel Brooks was shooting a sequence for his new film at the Music Hall in the afternoons that week. I put on my "I Belong Here" expression and showed up, which is how I came to be present in the room when Mel shot the Puttin' On the Ritz scene in Young Frankenstein, a scene this blog's friend Ken Levine has listed as among the top 5 funniest scenes in movie history. (And I am inclined to agree.)

Another day, Larry told me about going into a bar the evening before. Rod Serling sat down next to him and ordered a drink. Slowly the two men noticed each other. "Rod Serling?" Larry asked. "Seymour?" Rod asked back. Turned out Serling was a Seymour fan too. Larry was just tickled by it.

On August 8th, 1974, we had just finished taping my scripts for Vincent Price's Diary Of A Madman & Son Of Godzilla, when a news bulletin came over the studio monitors. I stood next to Larry Vincent in the studio at KHJ and watched Richard Nixon resign. Larry was very depressed by the event, fearing it boded ill for America. I was ecstatic to see the old bastard fleeing in disgrace.

During my time writing for Larry I came up with two new characters for him to play on the show, a biker hipster called "Mr. Cool" and "Ranger Bob", a forest ranger who dispensed insane forestry advice. I also created Seymour's Fairy Tales in which Seymour told horribly warped new versions of old children's favorites.

And then Larry was hospitalized. The show was cancelled. Larry gave me the task of writing the last two shows. The next to last show, for the film Octaman was never shot. Larry was simply too ill to do it, so a show was cobbled together out of old pieces on video at the last minute.

Larry came out of the hospital on a four-hour pass to shoot the last ever Seymour show. I appeared on that show as a guy sent from the city to tear down The Slimy Wall. We opened the studio doors and moved the set out into the parking lot for the last sketch, pretending that we'd been kicked out of the studio.

There was one more show to do. Seymour was signed to star in Seymour's Halloween Haunt at The John Wayne Theatre at Knott's Berry Farm, Halloween weekend. Since Larry was laid up in St. Joseph's Medical Center in Burbank, and Lynda was concerned with taking care of him, I was given the assignment to write the Knott's show. Gary Blair was going to be out of town that weekend, so I was also assigned to oversee the show for Seymour Productions that weekend. Moona Lisa & Chuck Jones the magician were also in the show, Knott's informed us, so I wrote them in, meeting with Jones, who was also supplying illusions for the show. Moona Lisa was tremendously easy to work with, happy just to be part of Larry's show, and willing to do what ever I wrote for her, and demanding nothing. Charming.

That Thursday, I picked Larry up at the hospital in Burbank and drove him to Knott's Berry Farm, installing him in a suite at a hotel adjoining the park, before scurrying over to the theatre to oversee the tech rehearsal while Larry relaxed. My job at the park that weekend was really just to see to it that Larry had as easy a time of it as possible. I didn't know Larry was dying, but he knew.

Before I could leave the hotel room to go to the rehearsal (Lynda was already at the rehearsal.), Larry stopped me. "Douglas, I have to tell you something. You've been a good friend to me, and I appreciate it. I love you, my friend." And he hugged me. I was embarrassed and kept mumbling that I knew it and he didn't need to say it, but Larry said, "No, I do need to say it." I didn't know it then, that he was taking care of business, making sure he'd said the things he wanted to say to his loved ones while he still could. Though I was about as uncomfortable as I could possibly have been at the time, afterwards, in the years that have followed, I have always been very deeply glad that Larry made a point of opening his heart to me, and letting me know I had earned a place in it.

Doing the show turned out to be the best medicine for Larry. He rallied that weekend, and rose to the occasion so well. He enjoyed himself tremendously. Between performances we would go out on an electric cart, toodling around the park, going on rides. As Seymour he would elaborately take cuts in line. "Look over there!" he'd yell, pointing away, and then we'd sprint up to the front and push on to the ride. "So long, suckers." He would call as we rolled into the ride, and everybody had a great time.

Closing night Larry had pizza delivered backstage for everybody working on the show, out of his own pocket. He entertained the friends of mine that came to the shows in his dressing room. He seemed to have time and energy for everybody. I remember sitting in that dressing room, listening to him talk about his experiences understudying Kirk Douglas on Broadway, and about the time, as a college student, that Boris Karloff had come and addressed them.

But Larry's rally lasted only about a month and he was back in the hospital. I came to see him as often as I could, until he was moved into intensive care and only family could come. It was Gary Blair who finally told me Larry was dying. It seemed hard to believe. He was only 50. These days I am 57, and I'm way too young to die. For Heaven's sake, Tallulah is 110, and seems set on outliving all of us.

Finally the terrible day came. I was living in Redondo Beach, next door to my aforementioned friend David Tarling (Who also took the Knott's Berry Farm pictures above, of Larry's last-ever show.) and his wife Mary. (David would better Larry, or perhaps worse him, by dying at age 38.) When I got up one day, there was a note tacked to my front door that Mary had left before going to work. It just said three little words: "Larry is dead." The pain of that loss is still sharp today.

It just isn't right. Larry should still be here, crotchety and funny at 82. We should have had a lot more laughs together. I can't imagine what other paths my life and my career would have taken had Larry Vincent not died so young, but I know I miss my friend still. He leers down at me from pictures on my wall, and, thanks to his loyal, devoted fans who loved him too, I have audio tapes to hear him again, though I know of no existing video tape of "Seymour", but I never give up hope video will turn up. Meanwhile, I have my DVD of The Incredible Two-Headed Transplant, and will get the Mission: Impossible DVD when it hits Amazon in two months, and he's in The Apple Dumpling Gang also.

In 1976, in a conversation that will forever be one the supreme highlights of my life, Groucho Marx, or, as I think of him, God, told me he had seen some of my Seymour shows and that he thought I was a funny writer. Groucho was a Seymour fan!